Strung Out - Playing with Line Strings

The job of an editor comes down to retaining and managing large amounts of footage. Many have developed systems for managing and organising the footage. Line stings is one these methods.

In many ways, the job of an editor comes down to retaining or managing a large amount of footage. You either have a great memory for a whole host of details, or you develop systems for managing the material so you can easily access your options.

Patryk Czekalski put it well:

“Ultimately, in TV, I feel that a lot of it is about the coverage, and in film, most of it is about performance.

It can differ how you prep dailies on a TV show versus a feature film—the emphasis on covering the scene is a lot greater in TV. You're trying to cover every possible angle to make sure the scene works and to address the notes the editor will later get from the execs.

Whereas on a feature film, because it’s the director’s vision, they often know exactly—especially experienced directors—how they want to cut the scene in their head. So instead of covering it from every angle, they’ll pick a few setups that push the story forward, and shoot take after take of that same angle, trying to capture a range of performances based on what they’re aiming for in the scene. Later, they’ll shape the character’s performance in the edit.

I think in television, on most shows, it would be very hard to shoot 20 or more takes due to time pressure.

That leads me to the assistant’s job: breaking down all that footage in an accessible way. For an editor to compare the same line from every take and angle, there needs to be a system for reviewing those lines. Some editors use ScriptSync, some use line strings or breakdowns. It varies, but every feature film editor I’ve worked with has had some method of organising the footage to compare and assess lines and beats quickly.

And it’s also so that when the director comes into the cutting room and wants to see all the versions of a specific line, the editor can, within seconds, hit play on that one line across every take and angle.”

Different editors have different methods of managing and organising the material they have at their disposal. These methods often depend on the resources available. There’s a big difference between an editor working alone with no assistant, and one working with a First Assistant Editor, a Second, and a Trainee.

The size of a team, the resources and the amount of time available to organise and prepare for the editor, has to adapt based on the size of the production.

London Via Limerick

The following is an interview I did for Assembled magazine. Issue Number 05 of Assembled, the magazine from Irish Screen Editors, has an international flavour featuring an interview with with Irish post-producer Clodagh McCarthy; Iranian film editor Hamid Najafirad; Patryk; and a look at the international co-production, The Apprentice – set in America, …

A Word About ScriptSync

Before I discuss line strings, a word about ScriptSync. ScriptSync is an Avid application that allows you to line up takes against the scene’s script, similar to how the script supervisor lines up takes in the lined script provided from set. This essentially lets the editor jump to a specific line in a take—or skim through all available options.

Although I’ve used ScriptSync a few times, I’ve never worked on a project where it was used for the entire film—only for selected, larger scenes. Even with technological advancements, it remains time-consuming and involves breaking down each take wherever the action restarts.

For those interested in learning more about script sync, Jack Brown, AKA The Avid Assistant does a great run through of how to use the app.

Line Strings

Line strings are a mainstay for many high-end editors. Put simply, a line string (or "string-out") is when an assistant editor breaks down footage line by line—literally stringing together every iteration of a line in a scene, one after another, until you have a long sequence of just that line being spoken.

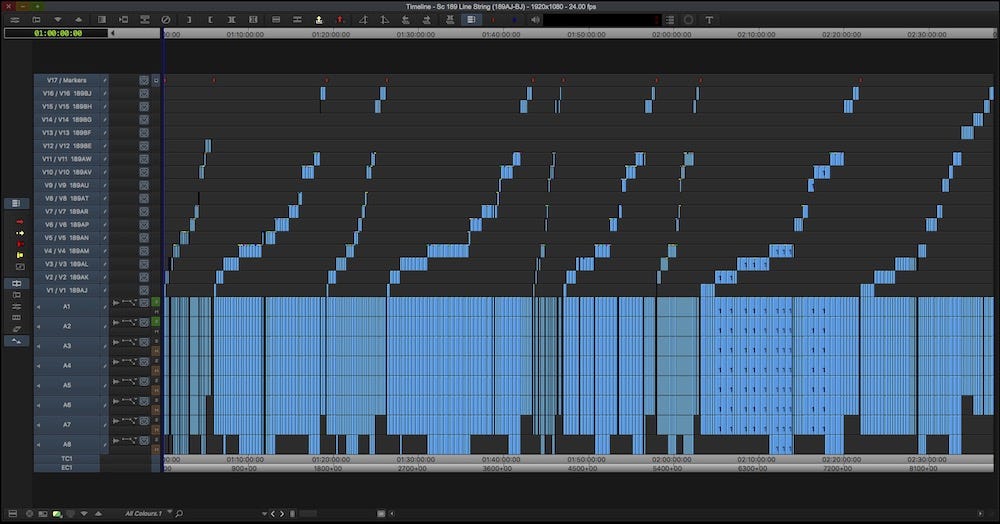

Editors who use this method have varying preferences. Some prefer it strictly line by line, others work in two-line pairs, and some in larger chunks of dialogue. Whatever the approach, line strings are incredibly time-consuming to produce. I’ve spent days stringing out lines for a single scene in the past. Very few editors have enough assistants to make the process worthwhile. Although, that being said, smaller productions tend to have a lot less lines to contend with, as this sequence of line strings from a scene in Mission Impossible shows.

For many, the benefit of a line string doesn’t justify the effort. It can feel like a waste of time. Still, there’s something interesting, even melodic, about listening to every variation of a particular line and getting a feel for performance differences. On productions like the ones Patryk describes, where there might be 30 takes, a method for analysing subtle differences becomes vital to achieving the best performance.

Finding My Own Method

There are many ways to organise rushes, and no single right answer. On a recent re-read of Art of the Cut: Volume II by Steve Hullfish, I was struck by how differently editors think about and manage their footage.

Ultimately, each editor has to figure out their own system, tailored to their workflow and resources. I’ve recently been exploring ways to better break down my own rushes—striking a balance between including all the relevant data (notes from the script supervisor, first impressions, technical metadata) and making the system scalable. That scalability has become especially important: I want a process that works both when I’m solo and when I have a team of assistants working with me who can build on it.

I’ve also focused on efficiency. On my current project, I’ve combined viewing rushes with several other tasks. I watch all footage in a long string-out, marking the start of each take with one colour and flagging key issues with others. I include as much metadata as time allows. Then, using a Markers Matchback macro (see my previous post, below), I transfer those markers back to the original sub or group clips in the scene bin—eliminating duplicated work.

We certainly don’t have the resources on my current production to do full line strings. But when I recently had to do one for a scene, I wondered if I could adapt my current method to create a more resource-friendly version for the future.

One idea I experimented with came from Rob Hall (The King’s Man, Fall), via his Art of the Cut interview:

“We wrote a number for each line of dialogue in the scene, and the assistants went through each take, adding a marker with the corresponding number whenever that line started. If I wanted to look at a particular line or delivery, I could just skim through the markers and sort them by number.”

What Does the Future Hold?

This may all become moot as advances in AI and transcription technology accelerate. The ability to automatically line up every iteration of a line could make line strings obsolete.

Before anyone raises a frustrated finger, let’s be clear: line strings are exactly the kind of task we should automate. A data scientist once said, “The job you want AI to do is the job you wouldn’t give to a trainee.” Line strings may have once been a rite of passage, but nobody enjoyed doing them. This is precisely the kind of workflow improvement we should embrace.

Personally, I’ve cut a few scenes using transcription tools, and I love the ability to reference the script in a separate window and highlight in/out points directly from the text. It helps me learn the script, spot deviations in performance, and overall, I believe it adds both speed and creativity to the edit.

That said, the tech still isn’t quite there yet for large-scale use. In my experience, Avid’s current AI tools are still a bit clunky and prone to crashing. But I have no doubt that in the next few years, these tools will become a standard part of the editorial toolkit.

For anyone interested in giving it a try, here’s The Avid Assistants run through of how it works (thanks Jack)