Walker Week

One person that I always make time to listen to is Joe Walker. With a few interviews this week from him talking about his work on Dune II, I deep dived into previous interviews for some insights.

One person I always make time for is Joe Walker. Walker, the editor of films such as Hunger, 12 Years a Slave, Sicario, and the Dune movies, is not only one of the best editors that we have today but also, by all accounts, a genuine gentleman. He seems endlessly enthusiastic about sharing his knowledge and craft with the broader editorial community. The lengths he goes to impart his insights are commendable, and I always gain something valuable from any interview he gives.

Recently, Joe has shared several wonderful interviews about his work on Dune II, released earlier this year. I highly recommend his interviews with Cut Daily Newsletter and The Editing Podcast; where he breaks down the sandworm scene from the Dune II.

This week, I thought I’d revisit a few of his earlier interviews to highlight some of the great insights he offers on the craft.

12 Years A Slave: Art of the Cut

Funnily enough it was Lupita Nyong’o Oscar speech, where she thanked Joe Walker personally, which kicked off a curiosity in US editor Steve Hullfish to interview Walker. This Skype interview for ProVideo Coalition spawned the podcast series Art of the Cut, which has since gone on to have multiple series and two books (the second book, has just been published if you are in the mood for some Christmas stocking filler list.)

“The things that excite me about working with Steve’s material – and “12 years” is really a good example of it – is that I love working with performance and music and image and sound and all that, but you also get to work with time. That’s a super-power unique to editing. So there are flashbacks and some sequences or shots in “12 years” that are held for a very long time which allow the audience to kind of invest and really study an image, but you have to balance that with a commercial sense and landscape things so that it doesn’t feel like artistic indulgence, but serves the story. The original book and the screenplay were chronological. The driving force was the calendar. After filming finished, we worked together for 10 weeks. The exploration began when we realised that this might not be the best way to drive the story. And maybe the better way is through following the expressive inner world of Solomon. That led us down a path of flashbacks. There were a few imperatives that we felt we had to obey. One was that we needed to immerse ourselves in the slave experience at the beginning and that we need him in chains by the end of reel one. And in serving that, it loosened up the timeline so that we could tell some elements of the story in the rear-view mirror. “

“What I mean about landscaping, is if you take a scene like the hanging scene, Steve had made a choice. He loved that scene in the book and could see it immediately. One of the ideas he’d sculpted into it was that when he and Sean (Bobbitt, the DP) had been working in the deepest gold mine in South Africa for an art piece called “Western Deep” (2002) he’d noticed that the workers tended not to make eye contact with them. To anyone who was in authority, there was no challenging gaze, they moved as ghosts around them. So you have Solomon left hanging because he’s caught between two masters. One person can’t hang him and the other person can’t cut him down – a casual nightmare taking place within beautiful countryside. That was Steve’s idea of what he wanted as the centerpiece of the sequence. But, if everything is slow up to that point, or after it, it would just feel like artistic indulgence. So what I mean by landscaping is we compress time enormously before it. You see Solomon waiting for the horsemen to arrive, but you don’t see them fully arrive, you don’t see them bind his hands and feet – all this was shot, but not used. When he’s strung up, it’s all happening way too quickly. It’s all racing and we’re sort of ahead of the audience. Then the music stops and we stand back, we’re on a wide shot and we let it breathe. Then after the event we’re also compressing time, so that when the Benedict Cumberbatch character – Master Ford – arrives and cuts him down, he hacks into the rope and we don’t even see Solomon falling to the ground, it just cuts straight into another shot where time’s moved on and he’s lying on the floor of an opulent hallway. You kind of manipulate time so you’re a little ahead of the audience and then you can stop, slow down and use as a soundtrack the rise and fall of the cicadas. We hold that shot for an agonizing time so that hopefully it provokes a response from the audience… that they are witnessing something real, disturbing, and hopefully it makes you just want to stand up and intervene.”

“There’s a strange trick, that if you put a border around things, without the intervention of cutting, or the intervention of music, then you’re sort of conning the audience into thinking they’re watching something real. There’s no safety net. It’s a little bit like what you might experience in an art gallery. You’re presented with something with a border around it, a frame and you’re initially attached to it, then you detach, then there’s another wave of interest where you’re more glued. That’s something we discovered on “Hunger” where we used a seventeen and a half minute long wide shot of just two people talking. And that too was very landscaped because we’d avoided dialog in the first third of the movie completely. It’s just a visual and sensory increase in violence between two sides in a prison and then you’re really ready for someone to talk about the issues. We studied the audience’s reaction to that scene, which is that they do detach, but then they come back even more invested and even more curious. There’s an incredible tension to it, by not cutting.”

“[One lesson that Walker learned from his mentor, Aidan Fisher] was about not cutting. It’s not like I apply this rule to everything, Steve, like yourself, I’m sure certain things apply to certain projects and you can’t use the same schtick all the time, but in his case a lesson I really learned was that he let me cut a sequence and it would be a three-shot and then singles and I’d merrily get stuck in the singles. He’d look at it and say, “You’re not getting any more from the singles than you are from keeping it as a three-shot, and with the three-shot you see all of the reactions. And I’d look at the three-shot and see that he was right. It was a great performance… an ensemble performance. The attitude was “Just because they shot it doesn’t mean you HAVE to use it’. That was a real lesson for me.”

Sicario: Art of the Cut

“In terms of sound design, I think a really good sequence to talk about is the night vision sequence. It almost sounds like it has a musical soundtrack, but actually it doesn’t, not until the last possible moment. There’s music in the lead up to the scene where all the forces are amassing together for the finale. They’re all on the hillside and they put on their visors, the music stops and they walk down the hill into darkness. It’s all very carefully choreographed. We spent hours in the edit recording my assistant in the next room on a walkie-talkie, using a ZOOM recorder, just coming up with improvised dialogue. The idea was to use dialogue almost as a sound effect. We always had a sense of this external operation, which can be very chilling when you’ve got a shot of Benicio (Del Toro, playing Alejandro) disappearing into the house and the drone pilot is saying “We’re going blind.” It’s got this sinister connotation that “as much as we *can’t* see what you’re about to do, we don’t *want* to see what you’re about to do.”

“To help with the sound design, buried in the seventh channel on one piece of sync I found this incredible whistling noise where the signal from the wireless lav mic wasn’t being received properly. We called it the guitar solo because it was this high, whining atonal melody as they’re walking down the hill, which emphasized the imperfection of their communication in the dark. Alan Murray’s team really brought some wonderful extra colors into that, so it just kept building and building and you sort of don’t even realize that there’s no music in that sequence. It’s very tense and it’s all to do with hard, sudden cuts that they think they see somebody in the background and a gun is lifted very quickly. It’s got interestingly uneven pacing… at least I think so.”

“And with the walkie talkie, you get great distortion which adds a level of panic. I have a memory of the original “Alien” movie that one of the really tense things when they explore the planet and discover these egg shapes, one of the things that really induces fear is that you can’t hear or see well. You can barely hear the crackly voices over the headsets and the video feed of what they’re seeing is indistinct. It adds a horrible vulnerability that they’re out there and hard to reach, without clear lines of communication.”

Team Deakins Podcast Interview with Joe Walker

Dune: A Frame IO Interview

“Both in the book and in the film there was this concept of “the Voice,” which is a hypnotic command, and that took a little while to get right. I think the ingredients and the ideas for that came out of lots of discussions and trying things out. Very early, the first idea was a bass thump that went with the Voice and, again, I can’t say whose idea it was, but we came up with the idea that the Bene Gesserit voices should be summoned and you should be able to hear the ancestry.”

“For that, we recorded two or three people with Jean Gilpin, who’s amazing and just did endless sessions for us. At one point we had Marianne Faithfull, who wasn’t well at the time, but she recorded some stuff for us. You can just hear her actually in the wake of Charlotte Rampling’s voice, which gives me great pleasure because I think they were old drinking buddies in the sixties back on King’s Road.”

“There’s a moment where they arrive in the desert, and they’re on their own, and Lady Jessica and Paul have got to traverse the desert, find the Fremen, and I needed in story terms a strong need to say that the next obstacle will be the worms. We are in the deep desert, and these things are the size of skyscrapers, and they follow rhythmic noise. I felt like it was important to make a big statement.

“Denis had shot this extraordinary landscape looking out over expansive sand flats, and it’s 17 seconds long. Which it doesn’t sound like a lot, but actually, at that point in a film, you’re very conscious of the fact that your audience is waiting for you to get a wiggle on and resolve this story. They know it’s going to resolve; they just don’t know how and we’ve got this last big obstacle before there’s hopefully a resolution. So it’s a little bit daring to put in a shot for 17 seconds, especially when it’s in the initial stages, and it’s just a plate shot. I have to keep saying, “It’s going to be fantastic!” even though at that point it’s just the plate shot; it’s just some landscape of the desert.”

“I keep saying, “We need to feel the music come to an end. Then we need to feel like a roar underneath and then wait for it and then erupt and then collapse and then see the collapse and then cut.” It has to have four or five beats within the one shot, which in the initial stages, it’s just a beautiful plate of the desert. It doesn’t have that narrative element. “

“So how do you build that up? At that stage, we are using temp tracks with the sound team. I’m saying, “Okay, this is what it’s going to be like.” and I am putting a little red dot and saying, “That’s when we first see the worm erupt; that’s where we’re going to see the sand collapsed behind.” You build it up with the use of the team.”

“I’m going to depart from this point for just a moment to say that one of my favorite moments on cutting Dune was working with Hans (Zimmer). I have collaborated with him so many times, and at one point, he was noodling around on the keyboard, and he was trying to find something, and I just said, “Hans, what are you actually looking for?” And he said, “I’m looking for a tune with the efficiency of the word ‘fuck’.” [Laughs] It’s a very efficient word; it’s international.”

Dune II : Cut/Daily Newsletter

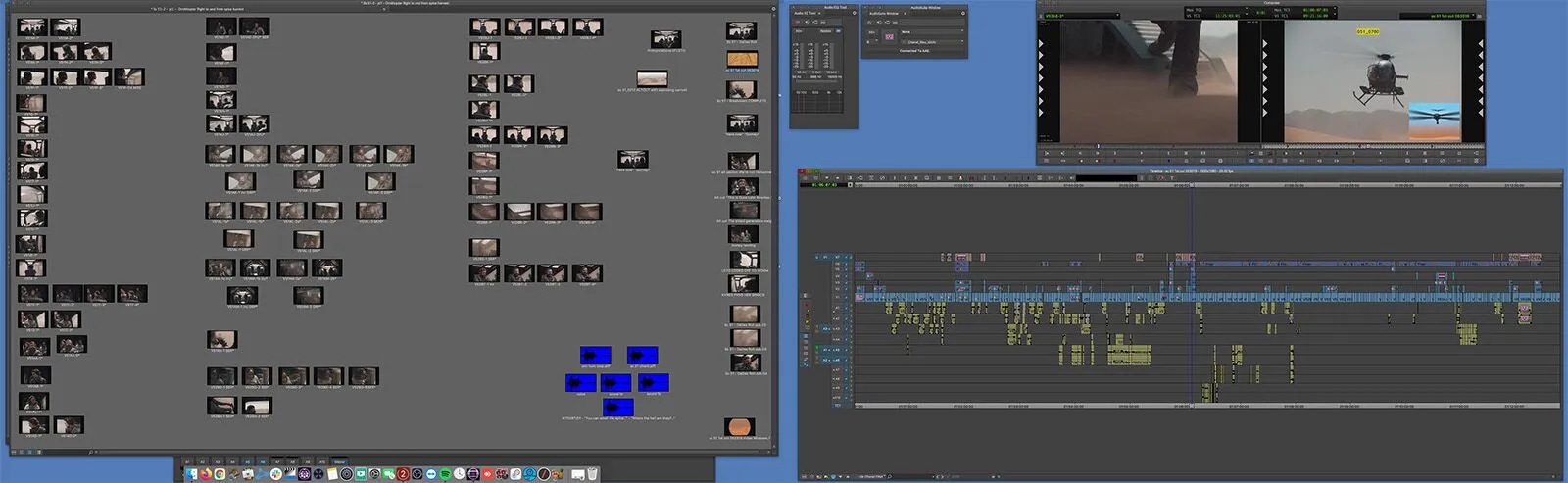

“I cut the last three films at home, so I do have the incentive of making the place organised and myself presentable before everyone arrives at 9. I brew coffee in a stovetop pot. I got a director into trouble with this. He was at a Studio boss’s house for breakfast and said the coffee was as good as cutting room coffee. His hostess was offended, but he meant it as a big compliment.”

“I have an hour or two alone at the Avid before the day starts, and I go over scenes from the previous day. In the evening I’ll take a break, go upstairs and watch half an episode of Dance Moms, then come back and carry on for an hour or two. I love what I do, but it takes time. At home, I can throw everything I’ve got at it without having to chew pizza somewhere joyless.”

“I started using a Pomodoro egg timer to keep me away from the internet. I set it, stay on track for 50 minutes, then run free for 5, and so on. These optimum periods were learned at school, I think. Chris Voutsinas, my long-term 1st Assistant, is a great cook so I relish the days when he has the time to knock something up.”

“I could see the generational divide when the editing community moved to digital in the 90s.

“The long in-between period working with material shot on tape removed a lot of the pleasures of the process, like viewing projected images all day on a flatbed. So I saw how resistant the older Editors were to the change. Having to quickly grapple with editing on all the tape formats, the thing that worked for me was learning how to do something by actually wanting to do it. Only when you needed to do a cross-fade in a sequence did it move into muscle memory, allied with will. Until that happened, it felt like commanding horses with a pair of rubber bands. So I shot a short film on tape and forced myself to edit it. Things fused in my head pretty quickly.”

“You never know where your next break is going to happen. Until then, keep doing the best work you possibly can, and for sure, someone will notice. If nothing else, you have to stay at your desk or the muses won’t know where to find you. “

I love Joe!